There’s a Zapatista creation story that describes two gods, Ik’al and Votán, who are attached at their backs, each facing away from the other, and can’t figure out how to walk. But as they wonder what to do with themselves, they discover that by taking turns asking questions, first “how” and then “where”, they could slowly move forward.

After their initial excitement about moving, Ik’al and Votán realize that they’ve come to a fork in the road. There is one short path, which they can see the end of, and one long one. So excited by the joy of walking, they decide to take the long road, even though they don’t know where it may lead. And since then, “the gods walk with questions and never stop…So then the true men and women learned that questions are for walking, not just for standing still.”

This summer, I got to spend a week in the Zapatista community of Oventik in the southernmost state of Mexico, Chiapas. I was there as part of the Zapatista Language School, but also to see how what I’d read about the Zapatistas translated into reality. Oventik also runs a secondary school (7th-9th grade), so I also had a lot of questions about how the rebel philosophy translated into pedagogy.

A week is not much time to learn anything, but here I’ve attempted to collect a handful of the conversations and ideas from my observations and classes.

Dignidad

“So you’re asking, what do we do if the students don’t care about their learning?” responds Alejandro, one of the education promotores who teaches in the school. I’ve just attempted to ask about discipline and classroom management, but unsure how to ask the question, ended up launching into a long-winded history of inequality and disengagement in U.S. public education. (I often found that my questions were the wrong questions, or only touched the edges of the real issue).

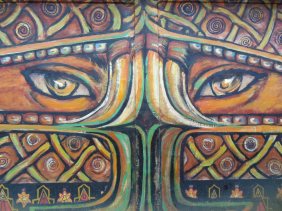

“Well, we give the students dignity and autonomy here, and they learn values that include them and their way of life. When there’s dignity, there’s a reason to learn,” this teacher explains to me. We are sitting on a little path between two dormitories made of cinderblock and wood, both covered in beautiful murals. “Plus, they know that they are part of our mission of constructing a new world.”

And it’s true that all the students I met there had a certain tranquility and thoughtfulness, even as they went about doing regular teenager things like playing soccer, gossiping, or singing along to pop songs. “You can tell a zapatista by the energy in their face”, explains Gabriel, one of our language school teachers. “La dignidad es visible”.

Dignity is a key idea in zapatismo that hadn’t stood out to me in my previous reading about the movement. It’s about feeling like a full, respected human being, even in the face of systems that are trying to erase your existence and way of life. Subcomandante Marcos explains that part of the Zapatista mission is to “rescue the histories of those from below that have been cast aside, and reposition them as the actual protagonists that they are…Dignity is taking what’s ours: life and land.”

Dignity is a key idea in zapatismo that hadn’t stood out to me in my previous reading about the movement. It’s about feeling like a full, respected human being, even in the face of systems that are trying to erase your existence and way of life. Subcomandante Marcos explains that part of the Zapatista mission is to “rescue the histories of those from below that have been cast aside, and reposition them as the actual protagonists that they are…Dignity is taking what’s ours: life and land.”

“Of course, they’re still teenagers,” adds Alejandro, the teacher. “So they get tired or bored. And that’s ok, so they just take a walk and come back”.

Autonomía

Alongside and hand-in-hand with dignity is the value of autonomy. One of the most striking ways that this manifested was in the lack of authoritarianism, particularly as a teacher. The 100 or so teenagers that studied at the school stayed in dormitories during the week before going back to their towns and families on weekends, and there were no chaperones or adults that stayed with them or told them what to do. There were clear community norms, such as times for meals or quiet time at night, but within those norms students were trusted to do what they needed to do- homework, washing clothes, going to class, etc.

The Zapatista movement arose from indigenous people who have been fighting to maintain their land and way of life for thousands of years. They are anti-capitalist and anti-neoliberal because those systems have attempted to -both literally and figuratively- destroy them in exchange for profit and control. Gabriel, our teacher with a grey beard and wise-man glasses, explained that “capitalism is incompatible with the idea of community, of different ways to live and interrelate. We are in resistance so that we can have a space in this world.”

The Zapatista movement arose from indigenous people who have been fighting to maintain their land and way of life for thousands of years. They are anti-capitalist and anti-neoliberal because those systems have attempted to -both literally and figuratively- destroy them in exchange for profit and control. Gabriel, our teacher with a grey beard and wise-man glasses, explained that “capitalism is incompatible with the idea of community, of different ways to live and interrelate. We are in resistance so that we can have a space in this world.”

One day we hiked to the top of a nearby mountain to have class, bringing along a thermos of dark Chiapas coffee and little bags of peanuts with chili. “In a capitalist society, ‘individualism’ means filling the role of the little cog the system needs you to be. But under that cog, in every person is a true person. Autonomy is uncovering that person.”

Within this context, you could tell that the students felt like they had a place and a role. “Siempre estamos en el contexta de la lucha”, Gabriel explained. We are always in the context of the struggle. The students know that they are part of something larger.

“What does it even mean to be rebellious at a school with rebelde in the name, that teaches rebel values?” joked one of the other American students. “That you want to wear a suit and go to business school?”

El camino

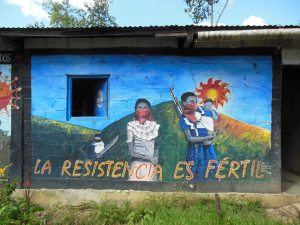

“El camino es lento, pero avanza” is a slogan painted on many of the  murals around Oventik. In terms of revolutionary philosophy, Zapatismo sees that many previous revolutionary movements have failed because they try to predict the future, saying “if we only do ______, then everything will be perfect”. Acknowledging that this is impossible, they instead move slowly along their path, making one move at a time and seeing what happens.

murals around Oventik. In terms of revolutionary philosophy, Zapatismo sees that many previous revolutionary movements have failed because they try to predict the future, saying “if we only do ______, then everything will be perfect”. Acknowledging that this is impossible, they instead move slowly along their path, making one move at a time and seeing what happens.

“The path to autonomy is not centralized”, Gabriel explained. “It goes community by community, as they get to know it. It’s not an accelerated rhythm, but rather the rhythm of the people.”

In terms of pedagogy, this relates rather nicely to the idea of inquiry, of asking a question and seeing where it takes you. Of trusting in our own learning processes, even as they may meander on their way to our main goal, and allowing students to explore and take pride in theirs.

The tsotsil class functioned in the same way: “Te’ oyoxuk, k’uxa elanik?” our teacher began. When we didn’t understand, she explained that this meant “good morning, how are you?”. When we still couldn’t answer, since neither of us knew any tsotsil, we answered in spanish, and our teacher translated. Jun ko’on, happy, translates to “of one heart”, or “my heart is whole”. So our teacher explained that its opposite, chkat ko’on, translates to “my heart is broken into many pieces”. Then we circled back: “So, how are you?”

The class continued in this way throughout the week, using simple questions to generate vocabulary and phrases we were interested in, circling back to practicing in dialogue those questions and their responses, and then from that generating new questions to continue the process.

The shell is a common image in Zapatismo, circling around while still moving forward (in fact, each of the 5 Zapatista autonomous communities are named caracoles, the Spanish word for shell). And as Ik’al and Votán found, following el camino is the joyous part of life, not arriving at fixed answers. It allows us to keep moving forward by asking questions.

-The story of Ik’al and Votán is from “The Story of Questions”, Zapatista Stories. Subcomandante Marcos, translated by Dinah Linvingstone. 2001, Katabasis Press.

-The quote from Subcomandante Marcos is from Viva Mexico!, a great documentary about La Otra Campaña.